|

Article By Michael D. King

By the 1730s, ranching had become vital to the region, transitioning to private ownership as Spanish missions declined. Central to our story is Margaret Borland, whose family journeyed from Ireland to Texas in the 1820s, driven by the promise of land and opportunity under John McMullen's impresario contract. The Heffernan family, including a young Margaret, faced immense challenges as they adapted to life in the untamed Coastal Bend region. Their remarkable resilience in overcoming cultural, environmental, and health obstacles set the stage for Margaret's significant role in the Texas cattle industry.

The episode also explores the tumultuous period of the Texas Revolution, highlighting the resilience and determination of Irish settlers. We follow the Heffernan family as they navigate the dangers posed by both Mexican and Texan forces, bandit attacks, and the harsh realities of war. Key events such as the Battle of Concepcion, the Goliad Declaration of Independence, and the infamous Goliad Massacre are examined for their impact on the settlers. The narrative shifts to the capture and negotiation involving Santa Anna, marking the end of hostilities and the beginning of a new era for Texas. We also touch upon the personal struggles and tragedies faced by the Heffernan family in the aftermath, including Margaret's life as a widow and single mother in the uncertain times of the Republic of Texas.

One of the pivotal moments in Margaret Borland's life was her journey along the Chisholm Trail, which played a crucial role in transforming Wichita into a bustling cow town. The Chisholm Trail, established by Jesse Chisholm in 1863, was instrumental in the Texas cattle trade. Margaret's journey along this trail is vividly recounted, highlighting the challenges and beauty encountered on the way to Wichita. Significant infrastructure developments like the Waco Suspension Bridge, which facilitated the cattle trade, are also discussed. Reflecting on Margaret's legacy and her untimely passing in 1873, the episode underscores the immense risks and hardships faced by those who dared to shape the early Texas cattle industry.

The story of Margaret Borland is not just one of personal triumph but also a testament to the broader historical context of the time. The Texas cattle industry was born in the Coastal Bend region, a geographical area of immense importance. The Heffernan family's journey from Ireland to Texas in 1829 marked the beginning of a wave of Irish immigration to the region and played a pivotal role in shaping the industry. The challenges they faced, from adapting to the new environment to dealing with cultural and health obstacles, highlight the resilience and determination required to build a new life in Texas. Margaret Borland's contributions to the Texas cattle industry were significant, but they were also marked by personal tragedy. Her life was shaped by the loss of her father during the Texas Revolution, the death of her first husband in a pistol duel, and the cholera epidemic that claimed her second husband. Despite these challenges, Margaret persevered, marrying Alexander Borland, one of the wealthiest cattle ranchers in South Texas. Together, they recognized Texas's potential as the hub of the American cattle industry, playing a significant role in its survival during the Civil War. These personal triumphs amidst adversity are a testament to Margaret's resilience and determination. The post-Civil War era brought new challenges, from a declining economy to the yellow fever epidemic of 1867. Margaret's resilience was again tested as she lost several family members to the epidemic, yet she continued to run the vast ranch by herself. Her determination was further demonstrated during the freak blizzard of 1871-72, which killed thousands of her cattle. Undeterred, Margaret organized a cattle drive to Kansas in 1873, marking the first time a woman led a trail drive. This monumental feat was a testament to her pioneering spirit and determination.

Margaret Borland's story is one of courage, resilience, and innovation. Her journey from Ireland to Texas, her contributions to the Texas cattle industry, and her personal triumphs and tragedies are a testament to the pioneering spirit of the Irish in Texas. This episode is rich in history, courage, and the indomitable spirit of those who shaped the early Texas cattle industry.

Join us for an episode that delves into the trailblazing legacy of Margaret Borland, a woman whose remarkable journey from Ireland to the heart of Texas cattle country continues to inspire. From the Spaniards introducing livestock in the 1690s to the critical role of ranching by the 1730s, we set the stage for Margaret's significant contributions. Experience the Heffernan family's resilience as they adapt to the rugged Coastal Bend region, navigating cultural, environmental, and health challenges that forged their indomitable spirit. Witness the harrowing trials during the Texas Revolution and follow Margaret's incredible journey along the Chisholm Trail, highlighting her role in transforming Wichita into a bustling cow town. Reflect on Margaret's legacy and the immense risks and hardships faced by those who dared to shape the early Texas cattle industry.

0 Comments

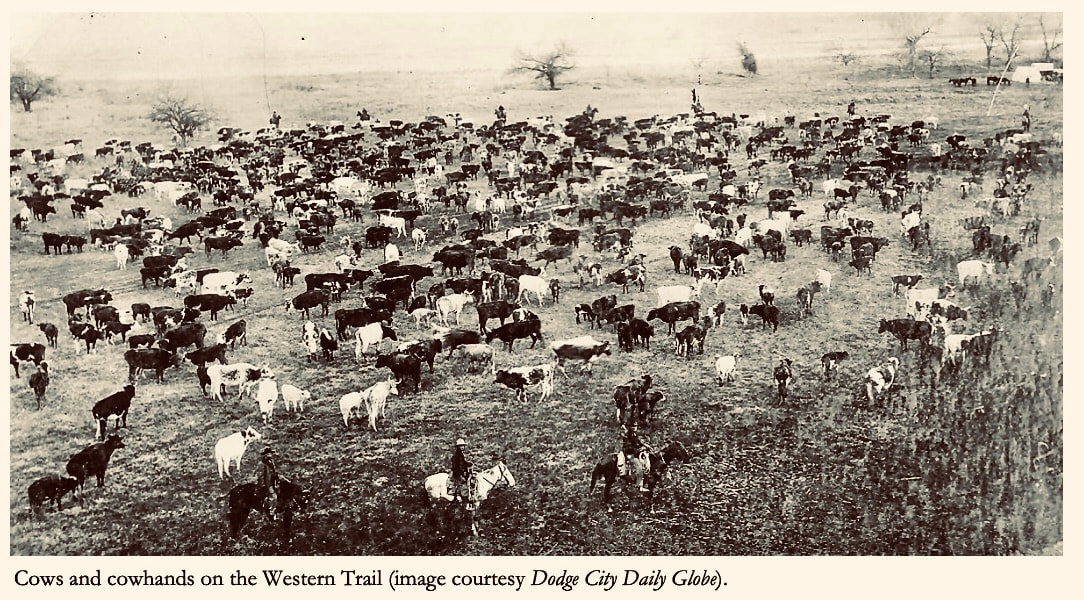

Article By Michael King Gambling, a game of chance that was not just a pastime but a cultural phenomenon, held a significant place in the lives of the buffalo hunters and cowboys who propelled America's westward expansion in the nineteenth century. Whether it was a game of Poker played on a blanket or a Faro bet placed in a saloon, the thrill and excitement of gambling shaped the social fabric of frontier towns like Dodge City. The popularity of gambling in the West can be attributed mainly to the fact that all those who left the relative safety and comfort of the East to seek fame and fortune on the frontier were, in a sense, natural-born gamblers. In the early West, gambling was not just a game but a profession, a risky and uncertain calling that mirrored the intensity and unpredictability of frontier life. The arrival of the Texas cattle drives in the 1870s was a game-changer for the gambling scene in the West. These drives brought a wave of gamblers and eager cowboys to the railhead towns in Kansas, such as Dodge City. The ensuing card games of faro, Monte, twenty-one, and Poker, played in establishments like the Lone Star, the Lady Gey, the Long Branch, and the Alamo, became a constant feature, almost outnumbering the cowboys who were their prey. Dodge City, the final and most infamous of the Kansas cattle towns, underwent a remarkable transformation. By 1875, it became the destination for Texas Longhorns, and over the next decade, the small, makeshift town on the prairie blossomed into a Cowboy Capital. It earned its notorious reputation as the 'Beautiful, Bibulous Babylon of the Frontier,' a vivid testament to the rapid growth and prevalence of vices like gambling on the frontier. Frontier towns like Dodge City were a buzzing hub of high-stakes games like Poker and Ferro, drawing in gamblers from all corners. Gambling was popular entertainment during the 19th century, particularly in frontier towns. The arrival of Texas cattle drives brought a new wave of gamblers, including professional figures like Richard Dick Clark. Faro, a game with a complex layout and unique roles for the dealer and casekeeper, was a crowd favorite. Another popular game was Spanish Monte, which the Texas Cowboys loved. The intricate world of gambling in the Old West was not just about entertainment; it was an integral part of the lifestyle. Poker, in particular, has a fascinating history in the Wild West. One famous poker game involved ex-governor Thomas Carney, who lost all his possessions to Colonel Charlie Norton. Quick-shooting gamblers like Bat Masterson, who became famous as frontier lawmen, frequented these games. The game, often leading to disputes and even shootings, was more than just a pastime; it was a risk-filled environment that could change one's destiny. But the games of the Wild West were not limited to Poker and Faro. The Spanish Monte, for example, was introduced to the card game scene at the conclusion of the Mexican War in 1847. These rough and unruly frontier guerrilla fighters learned the game well while occupying Mexico City, and soon, it was popular in Dodge City. This game's origin goes back to Spain, where the name means mountain or pile, as in a pile of cards. In addition to Poker and Monty, there was also the game of Keno, a lottery game that originated from a Chinese general who needed money to finance a war. This game found its way into Dodge City and was played in gambling houses known as Keno Dens. It involved players purchasing a ticket or card and placing small wagers to win a significant payoff if luck was on their side. The world of Wild West gambling was a thrilling and risky realm where every bet placed was more than just a game. It was a pivotal part of the culture and lifestyle of the era, shaping the destinies of many and creating legends that are remembered today. Whether it was a high-stakes poker game in Dodge City or a round of Spanish Monte among Texas cowboys, the allure of gambling in the Wild West continues to fascinate us today. The Game of FaroArticle by Michael King After the cattle were herded together and branded, the cowhands separated them into herds. Initially, the cattle owners themselves drove the herds. Eventually, they hired agents to drive the cattle to the market for a fee, usually $1 per head delivered to the market. Large herds of over 2,500 cattle went up the trail to Abilene, with many smaller herds also making the journey. Each drive required a foreman, a cook, and about fifteen cowboys. Edgar Rye describes the system of driving cattle along the trail in his book, "The Quirt and the Spur." The system of driving the cattle along the trail is exciting, especially to a tenderfoot who, for the first time, is permitted to watch the proceedings. On either side of the herd near the front rode two cowboys, called the pointers, who kept the leaders on the trail and shaped the course of the herd. The remainder of the boys, except the cook and his assistant, were busy keeping up the stragglers and cutting out the strays. The cook's assistant, the wrangler, kept the saddle ponies moving in the wake of the herd, and the cook brought up the rear with the "chuck" wagon. The cattle were driven in double column formation, like an army corps on the march, and the cowboys, riding up and down the line like so many officers, presented a novel sight. In this way, large bodies of cattle were driven over the trail. Under the guidance of the trail boss, the operation was managed with precision. Each cowboy, equipped with three to ten horses and their own riding and camping gear, was prepared for the journey. The team was armed against wild animals, rustlers, and potential attacks from Native Americans. With the labor force, horses, chuckwagon, and food supplies, the drive could handle about 1500 cattle, potentially earning more than $50,000 once the cattle reached the stockyards in Dodge City or Abilene and were ready for sale.

The Longhorns were used to living on grass, and usually, they could find enough along the trail. However, even though the herds were forbidden, they would sometimes be stopped for a day or two to fatten on lush grass in the Indian Territory. The herd, strung out on the trail, was a testament to the teamwork involved in cattle herding. Two trusted cowhands rode in the lead, one on each side, as pointers. Behind them, at intervals, rode the swingmen and the flank riders to keep the cattle in order. In the dusty rear were the unenvied drag men to prod the laggards. This was not just a group of individuals but a team, each member playing a crucial role in the drive's success. Scouts rode in front of the herd to select the best route. The path would vary depending on the availability of water and grass. It also relies on the year's season and how many herds had passed over the ground that year. Despite minor changes in the course, the herd always traveled north. Scouts also alerted the trail boss to dangers such as bad weather, hostile Native Americans, and outlaws. The trail boss had complete authority over all the cowhands and other employees on the trail. In his book Cattle Trade of the West and Southwest, Joseph McCoy describes cattle-herding along the trail in early cattle-herding along the trail. It should be noted that 1869 the chuck wagon had yet to be invented. A herd of one thousand cattle will stretch out from one to two miles while traveling on the trail and is a magnificent sight, inspiring the drover with enthusiasm akin to that enkindled in the breast of the military hero by the presence of marching columns of men. Confident cowboys are appointed to ride beside the leaders and control the herd, while others ride beside and behind, keeping everything in its place and moving on, the camp wagon and "cavvie yard" bringing up the rear. Their resilience and determination in the face of such a monumental task is truly inspiring. A large herd with several saddle horses could require 12 men or more. The trail boss, either a ranch crew member or a hired drover—organized and led the affair. He selected specific routes and rode ahead, searching for water, grass, and suitable campgrounds. The cook and his chuck wagon also moved forward of the herds to ensure the meals and "ink-black" coffee were ready when the cowboys settled in for the evening. The chuck wagon and the cook play a crucial role in the success of the drive, providing sustenance and comfort to the hardworking cowboys. Each cowhand had specific duties. Several highly skilled cowhands, known as pointers, also called point riders or lead riders, rode at the side of the lead cattle to direct the herd. The point man who rides near the front of the herd determines the direction, controls the speed, and gives the cattle something to follow. Larger herds sometimes necessitate the use of two-point men. A privileged position on the drive, this job is reserved for more experienced hands who know the country they travel to. Flankers, who rode beside the herd, kept the cattle from straying too far. The flank riders rode near the rear about two-thirds of the way back. Their role is to back the swing riders up and keep the cattle bunched, preventing the back of the herd from fanning out. Other cowhands rode in the rear, or drag position, to keep cattle from straying behind. The drag riders keep the herd moving, pushing the slower animals forward. Because of the exhausting work and insufferable dust, this unpleasant job is typically reserved for green cowboys. Swing riders ride closely along each side of the herd, about a third back from the point rider. They are responsible for keeping the herd together and constantly looking for animals that might try to break away. They are also instrumental in backing up the point riders as the herd turns. If the point man leaves his position, a swing rider will ride until he returns. Wranglers took care of the extra horses. Each cowhand took along several horses. The men would switch horses a few times a day to keep the horses from tiring. The wrangler cares for the driver's remuda, ensuring the horses are fed and doctored. He typically drives the horses with the wagon, as his secondary duties include helping the cook rustle firewood, unhook the team, or any other odd jobs around the camp.

By Keith Wondra

Article Reprinted by Authors Permission from the May 9, 2023, Dodge City Globe

As Frederic Young, Dodge City historian, wrote, “names of Dodge City’s saloons…ring in the ear like the clink of glass mugs on beer taps and the smash of empty glasses against varnished mahogany-the Alamo, the Long Branch, the Billiard Hall, the Alhambra, the Saratoga, the Occident,…the Crystal Palace, the Lone Star, the Old House, the Hub, the Sample Room, the Oasis, the Junction, the Green Front, the South Side, the Congress Hall, the Stock Exchange, and the St. James. Some saloons…were known only by their proprietors whose reputations were the only advertising needed- Hoover’s, Peacock’s, Beatty & Kelly’s, and Sturm’s. Some bars ran in connection with hotels, dance halls, and theaters- the Dodge House, the Lady Gay, the Varieties, the Comique, and the Opera House.”

Many consider Hoover and McDonald’s Liquor Store and Saloon, which opened in 1872, the first saloon and business in Dodge City. It was south of the railroad tracks on Trail Street, east of Third Avenue. By the end of 1872, five of the thirteen wood-frame buildings in Dodge City were saloons. George Hoover and John G. McDonald moved their saloon and liquor store to the vibrant North Front Street a year later.

Early Dodge City saloons included gambling within the saloons. South of the tracks had women and music. They were also one-room shacks with dirt floors while serving watered-down drinks, mainly whiskey. The railroad's arrival in 1872 allowed saloon owners to update their establishments with fancy wooden bars, artwork, and billiard tables. The railroad also brought in brandy, champagne, wine, and various types of whiskey. More than mere watering holes, the early Dodge City saloons were the heart of a vibrant community. Initially serving the needs of buffalo hunters, their clientele expanded with the arrival of the cattle trade in 1875. This shift was not just a business decision but a reflection of the saloons' role in the community. They were more than just businesses; they were a part of the fabric of Dodge City, fostering a sense of belonging among the cowboys by naming several of their establishments after Texas names and places such as the Alamo, the Alhambra, and the Lone Star.

In 1877 alone, there were 11 saloons, with the most famous being the Long Branch. D. D. Colley and James F. Manion opened it in 1876 near the northeast corner of Second Avenue and Front Street. Two years later, Chalkley Beeson and William Harris bought it and turned it into a refined place with an air of sophistication. Since dancing was prohibited north of the tracks, Chalkley Beeson’s five-piece orchestra provided entertainment, later becoming the famous Dodge City Cowboy Band. The Long Branch served alcohol, Anheuser Busch beer, lemonade, milk, sarsaparilla, and tea. In February 1883, Luke Short bought Beeson’s interests in the Long Branch and partnered with William Harris. In November, Harris and Short sold the Long Branch to Roy Drake and Frank Warren, who owned it until 1885.

On the south side of the tracks, where dancing and soiled doves were allowed, the most famous saloon was the Lady Gay Dance Hall and Saloon. Jim Masterson, brother of Bat Masterson and Ben Springer, opened the Lady Gay in April 1877 on the southeast corner of Second Avenue and Trail Street. The interior consisted of a platform for an orchestra on one end with a bar on the other. On July 4, 1878, the Comique Theater opened and was attached to the Lady Gay. In 1881, Ben Springer sold his portion of the Lady Gay to A. J. Peacock, an owner of several Dodge City saloons. The Lady Gay was bought in August 1881 by Brick Bond and Tom Nixon and renamed the Bond & Nixon Old Stand.

By the early 1880s, prohibition had come to Dodge, and several saloon owners had converted their businesses to drug stores and restaurants. This included the Stock Exchange Saloon, which became a drug store, and the Lone Star Saloon, which became Delmonico’s Restaurant. By 1885, the cattle trade had left Dodge, and temperance leaders were trying to close the saloons. The November 27 and December 8, 1885 fires burned down the wood buildings on Front Street and closed the saloons.

Dodge City Saloon War of 1883

The Dodge City War of 1883 is the story of a bloodless conflict between a gambler named Luke Short and the political structures of Dodge City, who tried to force Short to close the Long Branch Saloon and leave town. Narrated by Brad Smalley, the incident was filled with ominous possibilities for violence and brought several of the most infamous gunfighters in the history of the Old West into Dodge City to seek justice for their friend – Luke Short. The event is best remembered because it produced one of the most iconic photos of gamblers and gunfighters. This photo, taken in celebration of their victory over the political structures in Dodge City, is known as the Peace Commission and stands as a testament to their courage and unity.

By Michael King Dodge City, a place of monumental historical significance, was founded partly due to buffalo hunting. However, the hunting only started after the buffalo became nearly extinct due to mass slaughter. At this point, Dodge City needed another source of income to survive. Fortunately, circumstances in other parts of the country ultimately provided that source, profoundly shaping the city's history. Post-Civil War, Texas, a land known for its resilience, was ripe for the cattle industry to thrive. Despite the lack of labor and the disrepair of their ranches, the Texans, renowned for their resourcefulness, saw a potential solution to their problems in the wild native Longhorns. Their resilience in the face of adversity is truly inspiring. Ranchers in South Texas embarked on the challenging task of rounding up the Longhorns to sell to eastern buyers. However, they faced a significant obstacle in transporting the cattle to the cities, with no railroads built to where the cattle were and the prospect of driving them to market, causing them to lose too much weight. The ranchers were in a predicament. Their solution was to walk the cattle to the nearest railroad shipping point, usually in Kansas, and then let them ride the rest of the way. The Chisholm Trail, the most famous cattle trail, started in south Texas and ended in Abilene, Kansas. As eastern and central Kansas became more densely populated, local farmers resented the Texans who allowed their cattle to roam freely, which damaged the crops. The farmers also feared "Texas Fever," a disease carried by ticks on the Longhorn cattle, which was deadly to the local cattle. The farmers put up fences to keep out the foreign herds and protect their cattle, and the Kansas legislature passed quarantine laws to prevent Texas cattle from moving through certain parts of Kansas. The legislative action led to the discontinuation of the Chisholm Trail, and cattlemen began using the Western Trail from south Texas to Dodge City, where the Texas trade was more welcome. On the trail, the hardy Longhorns, with their remarkable resilience, grazed for food and spaced themselves by instinct as they moved along about 12 miles a day. Their ability to endure the long journey and harsh conditions is truly admirable. A steer could be driven from the starting point in Texas to Dodge for about 75 cents. The fifteen or so men employed for the drive were each paid thirty to forty dollars a month, so by the time they reached Dodge, $90 or more jingled in their pockets, and they were ready to spend it all on a good time. The first herds heading to Nebraska reached the point of rocks on the outskirts of Dodge City in 1875, marking the beginning of a significant economic boom. The Santa Fe Railroad Company acted quickly by constructing a large new stockyard, and Robert Wright dispatched agents down the trail to assure the drovers that Dodge was ready and waiting for them. Storekeepers purchased new merchandise to meet the needs and desires of the cattlemen and cowboys instead of buffalo hunters. Saloon keepers gave their businesses Texas-inspired names such as Nueces, Alamo, and Lone Star. On May 12, 1877, the first herd from the Red River arrived in Dodge, solidifying the economic importance of the cattle trade. The drives increased until the number of cattle peaked at half a million for one year. The city was buzzing with activity and prosperity, a testament to the success and excitement of the cattle trade. Robert Wright advertised his store as "the largest and fullest line of groceries and tobacco west of Kansas City. It offers everything from a paper of pins to a portable house. The store provides groceries and provisions for your camp, ranch, or farm, as well as clothing, hats, boots, shoes, underclothing, overalls, Studebaker wagons, Texas saddles, rifles, carbines, pistols, festive Bowie knives, and building hardware. The profits are $75,000 a year." Wright mentioned that it was common practice to send $50,000 shipments to banks in Leavenworth for deposit because Dodge had no bank. The store served people of various nationalities. Wright could comprehend and communicate in most Indian languages. Mr. Isaacson was fluent in French, while Samuels had Spanish, German, Russian, and Hebrew expertise. Merchants and saloon keepers knew that trail hands expected to have a good time when they reached town, so they were prepared to provide the right ingredients. The saloons varied from small one-room shanties with dirt floors to long wooden buildings with painted interiors, intricately carved mahogany bars, mirrors, and paintings. These frontier saloons offered more than just poor-quality alcohol and strong spirits. The saloons also provided fine liqueurs, brandies, and the latest mixed drinks. Ice was always readily available to ensure that beer would be served cold and enhance the drinking experience in the newly developed Cowtown. The Old House Saloon even advertised anchovies and Russian caviar on its cold lunch menu. Dodge City's cattle era lasted only ten years, from 1875 to 1885. However, these crucial years shaped its reputation and global renown. It was a time of transition, as the 'Queen of the Cowtowns' evolved into a thriving farming community and trade center, marking a new chapter in its history. Article By Michael King The Dodge City Rodeo has a captivating historical origin that sets it apart. It all began with the world premiere of the movie Dodge City' in 1939. Warner Brothers, the movie's producers, mandated that Dodge City be transformed into a western-themed town for the premiere. This included a requirement for an authentic rodeo to be held on the day of the premiere, April 1. Though they held a cowboy-style show at McCarty Stadium, there needed to be more time to prepare for a full-fledged rodeo by April 1. The "real" rodeo, the Boot Hill Roundup, had to wait until May. It was Dodge City's first annual rodeo. It lasted three days and was sponsored by the Great Southwest Free Fair Association, with Warner Brothers supplying much of the equipment. The final performance at McCarty Stadium on Sunday afternoon drew a crowd of 6000. The first rodeo event was a hit, as there's been a rodeo in some way, shape, or form every year since this emergent first effort. In 1950, Dodge City initiated a new festival, the Boot Hill Fiesta. The Fiesta was held in May, completely separate from the rodeo, and was a summertime affair. By 1960, the rodeo was known as the RCA Rodeo when it merged with the Boot Hill Fiesta. Together, they became Dodge City Days, held over three days during the summer. It later expanded to six days and is now ten days. In the 1970s, the rodeo portion of Dodge City Days nearly folded and was saved in 1977 when it was reorganized as the current Dodge City Days PRCA Roundup Rodeo. Ron Long served as its first president. The first reorganized rodeo had 175 contestants and paid out $8,200. Today, the Dodge City Rodeo has blossomed into a significant event. It occurs at the arena, east of 14th Avenue, just south of the Arkansas River. The five-day rodeo now boasts nearly 800 contestants, with pay-offs reaching an impressive $339,000. Dr. R.C. Trotter, who has been President of Roundup since 2003, has played a crucial role in this growth, committing 40 years of his life to Kansas' biggest rodeo, a Dodge City Days celebration staple. In his time with Roundup, the rodeo has blossomed. It's one of the top events in ProRodeo regarding contestant numbers and total payout. He credits the sponsors and fans for the success, but there's more to it. In its 35th year, Roundup Rodeo was enshrined into the ProRodeo Hall of Fame in Colorado Springs in July 2012. Trotter was on hand then, just as he is now. The commitment that comes with volunteerism is special. The more prominent festival, Dodge City Days, is sponsored by the Dodge City Area Chamber of Commerce. Their efforts have made Dodge City Days recognized as the second-largest community celebration in Kansas, topped only by the Wichita River Festival. Over 100,000 people attend at least one festival event, generating approximately three million dollars. However, the economic impact on Dodge City is about nine million dollars. The early pioneers like William F. Cody, Annie Oakley, Mabel Delong, William Pickett, Earl Bascom, and many more are at the heart of the rodeo's history. Their dedication and passion keep the rodeo spirit alive. It's the ranchers that genuinely support the legendary rodeos. Without our ranchers, we wouldn't have rodeo in the first place. As noted before, there are many complexions to rodeo. Some are the participants astonishing the gatherings in the stands; others are the timer technicians in the back, the rodeo clowns risking their lives in a barrel, and announcers moving the assemblage as they update them on the event. But when you think of it, rodeo is built by hard-working people with a passion. Like in the early days, people's livelihoods laboriously depends on ranchers. We have so many to thank for the history of rodeo. In conclusion, the history of rodeo is a testament to the enduring spirit of the cowboy. From its origins in the Wild West to its status as a professional sport, rodeo has undergone a fascinating evolution. The journey speaks to the resilience, courage, and innovation of those who have shaped this unique sport. As we look to the future, we can only anticipate that rodeo will continue to evolve, inspire, and thrill generations to come. For more information on the Dodge City Roundup Rodeo, visit the Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/DodgeCityRoundup/ or their Website at Dodge-City-Roundup-Rodeo. So, if you happen to be in the area, put on a hat and boots, and don't miss out on one of the top rodeos in the country, including Dodge City Days.

By Michael King

Dodge City, Kansas, is a quintessential American Wild West symbol. Its very name conjures images of dusty streets, gunfights, and saloons bustling with the ambitions and desperations of pioneers. But how did this iconic boomtown arise from the vast, untamed prairies of the West? To begin our story, we must delve into the rich tapestry of Dodge City's history, exploring its gritty beginnings and the visionary individuals who, with unwavering resilience, carved a community out of the frontier.

In the early 1870s, as the iron veins of the railroad stretched ever westward, Dodge City emerged as a beacon for those seeking opportunity. It began humbly with a solitary sod house belonging to Henry Sittler, the area's first known settler. Yet, it was only a short time before the entrepreneurial spirit of men like John MacDonald and George Hoover spurred the town's rapid growth. MacDonald, an early citizen and businessman, forged a pivotal partnership with Hoover, and together, they established the first saloon, planting the seeds of commerce in this nascent community.

Next came the Essington House, Dodge City's inaugural hotel, which became a cornerstone for the burgeoning town. The establishment's owner, J.M. Essington, met a dramatic end, a narrative arc emblematic of the unpredictable and often violent life on the frontier. Essington's demise led to him being among the first interred in the now-famous Boot Hill cemetery, marking another somber chapter in the town's development.

As we dive into the annals of Dodge City's past, we encounter figures like Frank Hopper, also known by the pseudonym Norf, whose written accounts helped to shape the town's early reputation. The nation learned of this wild town at the edge of civilization through his articles. Hopper's vivid descriptions of the saloons, businesses, and daily life in Dodge City provided a lens through which the rest of the country viewed the unfolding drama of the West. Businesses like Jacob Coller's general store and F.C. Zimmerman's gunsmith shop were instrumental in keeping Dodge City alive. These establishments, with their unwavering commitment, catered to the needs of buffalo hunters, soldiers, and travelers, supplying everything from clothing to firearms. The importance of such enterprises cannot be overstated; they were the town's lifeblood, facilitating its residents' survival and prosperity.

Interestingly, despite the contributions of both John MacDonald and George Hoover to the founding of Dodge City, historical records often favor Hoover's legacy over MacDonald's. This discrepancy in recognition is a point of contemplation, prompting questions about how history is recorded and the factors influencing who is remembered and who is forgotten.

The narrative of Dodge City begins by not merely recounting historical events; it breathes life into the stories of those who lived them. It invites readers to ponder the hardships, resilience, and triumphs of those who ventured into the unknown to forge a new life. The tale of Dodge City is not just one of economic opportunity but also of human endeavor against the backdrop of a wild and unforgiving landscape. In closing, Dodge City's legacy is as enduring as the legends that surround it. Its history is a testament to the determination of the pioneers who sought to tame the West and, in doing so, created a legend that continues to captivate the imagination. The enduring legacy of Dodge City is a significant part of American history, a testament to the determination of the pioneers who sought to tame the West and, in doing so, created a legend that continues to captivate the imagination. We encourage readers and historians to investigate deeper into Dodge City's annals, explore its citizens' enduring spirit, and appreciate the rich chronicles that shaped this American icon.

Most of the businessmen thought Webster's idea a good one. It would rescue businesses suffering from a slowing down of the cattle trade. Also, Dodge had always been a sporting town and a bullfight certainly would be different from the usual parade, races, prize fights, and hose-cart team competition. The Dodge City Democrat wrote of the event on June 28, 1884

A number of so-called good and moral people of the city have attempted to convey the impression... that there will be no bullfight... The reports were started by the same class of fanatical agitators who are eternally opposing every enterprise calculated to advertise Dodge and promote its growth and prosperity ... It is the same class of men who have for years done nothing but howl and kick and at the same time grow wealthy and fat.

Webster collected $10,000 from the merchants in two days to pay for the festivities. The investors formed the Dodge City Driving Park and Fair Association and elected Ham Bell as president and Webster as general manager. Webster started immediately making arrangements. He contacted W. K. Moore, an attorney in Mexico, who would secure the matadors. D. W. "Doc" Barton, who had driven the first trail herd to Dodge, agreed to scout the ranges and select the most ferocious Longhorn bulls. With his extensive knowledge of cattle, Barton spent days on the range, carefully observing and selecting the bulls that would provide the most thrilling and authentic bullfight experience. The Association bought forty acres of land at the city's west edge.

With a sense of urgency and commitment, they put up high wooden fences, planted trees, built corrals, chutes, a half-mile racetrack, and an amphitheater that would seat 2,500 spectators - all in less than two months. The speed and efficiency of the preparations were a testament to the town's unwavering determination to make the bullfight a reality, showcasing their resilience and commitment. As the news stories began to circulate, the determination of the Dodge City officials became evident. Reporters from New York, Chicago, St. Louis, San Franciso, Denver, and a dozen country newspapers booked rooms in the local hotels. The Santa Fe railroad announced it would run excursion trains from the East and the West to bring spectators to the Dodge City bullfight. Despite protests from groups concerned with the prevention of cruelty to animals and rumors that state authorities would stop the fight, the officials remained resolute. Governor Glick even expressed his interest in attending if the fight were held two days earlier. Townspeople at the time claimed that Webster received a telegram from the United States Attorney saying that bullfighting was against the law in the United States, to which the ex-mayor retorted, "Hell! Dodge City ain't in the United States." This bold and determined response highlighted the town's defiance in the face of potential legal issues. As the days before the fight dwindled, Barton rounded up the bulls and drove them into the new pens. The five bullfighters arrived with Attorney Moore, their sponsor. The town was buzzing with anticipation, taking on a festive air as the event drew closer, filling the air with a palpable sense of excitement and energy.

On July 4, 1884, the town was alive with the excitement of the Mexican bullfight. The dusty streets, the weathered clapboard houses, and the rowdy saloons all contributed to the allure of this wild western town. The arrival of the Mexican bullfighters added an exotic touch, and the preparations for the bullfight were a spectacle in their own right.

The bullfight held the entire town in its grip. Thousands of spectators, including cowboys, ladies, and children, filled the stands, eager for the thrilling spectacle. The matadors, adorned in flamboyant costumes, showcased their skills against the fierce bulls. The pinnacle of the event was the face-off between the slender Mexican matador, Gregorio Galardo, and the meanest bull in the West. The memory of this epic encounter, with its breathtaking display of courage and skill, still reverberates today among the citizens of Dodge City, connecting them to their rich history.

After the thrilling bullfight, Dodge City became even more unforgettable. The wild night that followed was filled with fights and gunplay, keeping the marshal and his deputies busy trying to maintain order. The marshal, a seasoned lawman with a reputation for fairness and quick action, and his deputies, a group of brave men who had seen their fair share of gunfights, were constantly on the move, breaking up fights and apprehending troublemakers. Despite the chaos, the town remained excited, the air crackling with the night's energy.

Yet, like all good things, the excitement eventually died down. The influx of visitors, while a boon for the local economy, also brought with it a wave of lawlessness and disorder. Having spent their money and nursed their hangovers, the cowhands left town. The painted ladies, who had been a colorful presence during the bullfight and the revelry that followed, also departed. The dust settled, and the town returned to its usual quiet state. In all its glory, the bullfight had left a lasting mark on Dodge City, a mark that would change the town's history forever. Keith Wondra, curator at Boot Hill Museum and Vice President of the Western Cattle Trail Association, Dodge City Chapter, will delve into the vibrant life of the legendary Ham Bell, an epitome of the Wild West spirit. This special presentation of Ham Bell's life will be held during Dodge City Days on July 31 at Boot Hill Museum starting at 2:00 P.M. On April 4, 1947, Hamilton 'Ham' Bell passed away. According to his obituary, he was one of the most influential men who lived in early Dodge City, shaping the community we know today. Boot Hill Museum curator Keith Wondra will talk about the life of this Dodge City pioneer, shedding light on his contributions to our local history. Born as Hannibal Bettler Belts in Washington County, Maryland, Ham embarked on a journey to Dodge City, Kansas, leaving an indelible mark on its economic and cultural life. In his early life, Bell was a restless jewelry store salesman who had mastered cleaning clocks. This skill would later pave his way to Kansas. He took Horace Greeley's famous advice, "Go West, young man, go west and grow up with the country," and embarked on a journey of self-discovery and reinvention. Ham Bell's arrival in Dodge City marked the beginning of his various ventures. His first business, a sod livery stable, grew into the largest structure in Western Kansas. Known far and wide as the Elephant Livery Stable, it became a meeting point for people throughout the region. Bell's entrepreneurial spirit did not stop there. He opened a dance hall and was the first to introduce the exotic Can Can dance to Dodge City. The dance quickly became the talk of the town, bridging the cultural gap between the frontier and the East Coast. Not just an entrepreneur, Ham Bell was also a respected lawman. His career in law enforcement spanned an impressive 36 years. Ham Bell's rule of never shooting his gun garnered him respect and admiration. His strategy was to draw his weapon in time to make the other man freeze, an approach that contributed to his survival in the volatile environment of the Wild West. Bell's political career was also noteworthy. He served two terms as mayor of Dodge City and two as a Ford County Commissioner. His unique physical attributes and charisma undoubtedly contributed to his political success. Beyond politics and law enforcement, Bell made significant contributions to modernizing Dodge City. He introduced the first women's restroom on the Santa Fe Trail and the first motorized ambulance and hearse in Dodge City. He also operated a furniture store and mortuary business, leaving a floral tribute on the casket of anyone who passed away in the city. Bell's adventurous life didn't stop there. He owned the first car dealership in southwest Kansas and operated a pet shop. When he passed away in 1947 at 94, he left behind a rich legacy and many stories that continue to captivate those interested in the history of the Wild West. The life of Ham Bell, a true pioneer, serves as a testament to the indomitable spirit of the Old West, painting a picture of a time of resilience, entrepreneurship, and cultural evolution. This presentation coincides with a temporary exhibit on the life of Ham Bell. We invite you to come and grab a coffee or even a sarsaparilla and help celebrate Ham's 171st birthday. Take advantage of this unique opportunity to learn about the life of a Wild West legend and explore Boot Hill Museum's special exhibit. We look forward to seeing you there!

In Dodge City, saloons were popular destinations for drovers to relax and quench their thirst after a long journey. The main road, Front Street, was lined with wooden shanties with porches where water barrels were kept in case of fire. South of the town was the infamous 'Red Light District,' a captivating area that was not only well-known for its three vices: whiskey, gambling, and prostitution, but also for the intriguing stories and characters it housed. This area, with its alluring mix of vices and captivating history, not only fueled the economy of Western Cattle Town but also formed a fascinating part of its history.

Keith Wondra, curator for Boot Hill Museum, tells us that the primary whiskey sold in Dodge City saloons was corn mashed, a staple of the Wild West. It had 40-50% ethyl alcohol by volume and was made from grain, water, and yeast. The production process involved mashing the corn, fermenting the mash, and then distilling the fermented mash. It was aged in new charred oak barrels and referred to as bourbon. During that period, almost every type of whiskey was called bourbon, regardless of where it came from, as long as it contained corn. However, one whiskey, known as the 'Old Sneak Head,' stood out for its unique ingredients and meticulous craftsmanship that would undoubtedly pique the interest of whiskey enthusiasts. Its ingredients included alcohol, tobacco, molasses, red Spanish peppers, and river water. Two rattlesnake heads were added to each barrel to give it spirit. The whiskey was ready to drink when the rattlesnake heads rose to the surface and floated after being dropped in a horseshoe, a process that was as fascinating as it was unique, adding a touch of mystery to its production. Saloon owners, driven by profit, resorted to a deceptive practice. They sold overnight whiskey, watered down to increase their profits. A gallon of whiskey cost $2.00, and a drink was sold for 25 cents, which meant the saloon owner made a profit of about 700%. The more they watered down the whiskey, the more profit they made, a practice that may have left a bitter taste in the mouths of those who sought a genuine whiskey experience. Between 1872 and 1876, it's estimated that 2,250 barrels of whiskey were consumed in Dodge City, which is the equivalent of approximately 70,875 gallons or 4,536,000 drinks. However, after the railroad reached Dodge City in 1872, a new era of drinking began. Saloons started selling not just whiskey but also beer, champagne, and wine, offering a diverse range of beverages. Join Keith Wondra on Wild West Podcast as we journey through time to uncover the captivating chronicles of Dodge City's early saloons. From dark, inexpensive origins to their influence in shaping the city's cultural and economic landscape, Keith guides us through every nook and cranny of these saloon stories, revealing fascinating details about these establishments that were Dodge City's lifeblood during its formative years. We discuss the infamous Saloon War of 1883 and its monumental impact on Dodge City and its economy. Original Story by Lynne Hewes Edited and Extended by Michael King

Contrary to Hollywood's glamorous fiction, singing cowboys were a genuine part of the earlier cattle drives, adding a touch of authenticity to cowboy culture. Long hours on horseback gave cowboys idle time to sing. Some carried harmonicas or even fiddles, but the human voice was the easiest and best instrument. Most started with old folk songs they had learned as kids, then changed the lyrics to fit their lives on the trail. This process of adaptation was not just about changing the words, but also about infusing the songs with their own experiences, emotions, and the unique challenges they faced as cowboys. Cattle drives were over by 1907 when historian John Lomax, a key figure in the preservation of American folk music, set out to study the cowboy's music. Lomax, known for his extensive field recordings and his efforts to document and preserve traditional American music, collected songs and ballads from any and everyone and put out advertisements in local papers. The response was nearly overwhelming. He compiled these songs three years later and published them as 'Songs of the Cowboy and other Frontier Ballads', a seminal work that significantly preserved and popularized cowboy music. E.C. Abbot, also known as "Teddy Blue," discussed cowboy songs in his autobiography, We Pointed Them North: Recollections of a Cowpuncher. Abbott wrote about his own singing on the trail. His book explained the popularity of singing this way: "Another thing about cowpunchers, they didn't have any radio or other forms of entertainment, and they got a big kick out of little things" (220). There was a practical reason for the song as well. Abbot wrote, "One reason I believe there were so many songs about cowboys," he wrote, "was the custom we had of singing to cattle on night herd. The singing was supposed to soothe them, and it did....I know that if you wasn't singing, any little sound in the night—it might be just a horse shaking himself-could make them leave the country, but if you were singing, they wouldn't notice it" Abbot talked about particular songs he said were his favorites, many of which had come from the Ozark Mountains. "I learned' The Little Black Bull' first," he wrote. "That's the oldest song on the range.... 'Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie' was another great song for a while, but it ended up just like a lot of songs on the radio today; they sung it to death...." (222-4). Sometimes, boredom with traditional lyrics led to new songs. Abbot wrote, 'After a while, you would run out of songs and start singing anything that came into your head. And that was how [new songs got started]'. This process of creating new songs out of boredom and improvisation was a testament to the creativity and resourcefulness of cowboys. It also contributed to the rich and diverse repertoire of cowboy songs, which ranged from traditional folk songs to original compositions. Sources

Abbot., E.C. and Helena Huntington Smith. We Pointed Them North: Recollections of a Cowpuncher. University of Oklahoma Press, 1939. Cecil, Randle, and Shelby Conine. “Singing Cowboys.” Country Music Project. https://sites.dwrl.utexas.edu/countrym usic/the-history/singing-cowboys/

When we think of the Old West, images of dusty streets, gunfights at high noon, and saloons bustling with gamblers and outlaws often come to mind. In this latest podcast episode, we journey to the heart of these legendary tales to the town of Abilene in the 19th century. This was a time when the frontier was more than just a place—it was a crucible of American character and spirit.

Abilene, Kansas, emerged as a significant cow town during the late 19th century. It was here that cattle drives ended and cowboys, fresh from the long and arduous journey up the Chisholm Trail, sought the pleasures of civilization, however rough-hewn it might have been. The cattle industry was the lifeblood of these towns, and Abilene was no exception. Cowboys and settlers alike depended on the economic stability that it provided, even as they navigated the lawlessness that seemed inherent to these burgeoning communities. Our episode delves into the lives of the hardy saloon keepers, shrewd gamblers, and notorious sporting women who were as much a part of Abilene's identity as the cattle that flowed through its streets. These individuals helped carve a town from the Kansas plains that was at once a symbol of prosperity and a beacon of the wild spirit that defined the era. They turned Abilene into an emblem of the untamed frontier, a place where opportunity and danger walked hand in hand. The challenge of maintaining law and order in such a place fell to men like Tom Smith and Wild Bill Hickok, whose names have become synonymous with Wild West justice. Our episode recounts how Smith, using his fists more than his guns, brought a measure of peace to the town, while Hickok's approach was more aligned with the legend he had become—his six-shooter often being the final word in disputes. The impact of these men on Abilene, and the frontier in general, cannot be overstated, as they sought to impose order on a landscape resistant to it. In listening to our episode, you'll hear firsthand accounts of epic showdowns, the complexities of the cattle drives, and the transformation of Abilene from a dusty village into a bustling hub of nightlife and vice. We aim to paint a vivid picture of this complex metamorphosis, exploring the thin line between civilization and lawlessness, and how the people of Abilene navigated it. As the episode concludes, we reflect on the enduring spirit of Abilene, inviting listeners to continue exploring the dusty trails and stormy skies of the Wild West's past. With every tale told and every account shared, we keep the history of the American frontier alive, inviting engagement from our listeners to shape the stories yet to come. So saddle up and join us on this historical adventure, as we stir the embers of a time when the West was truly wild, and every corner had a saga to share. Subscribe for more episodes that promise to ignite your imagination and transport you to the heart of the Old West, a time and place like no other in American history.

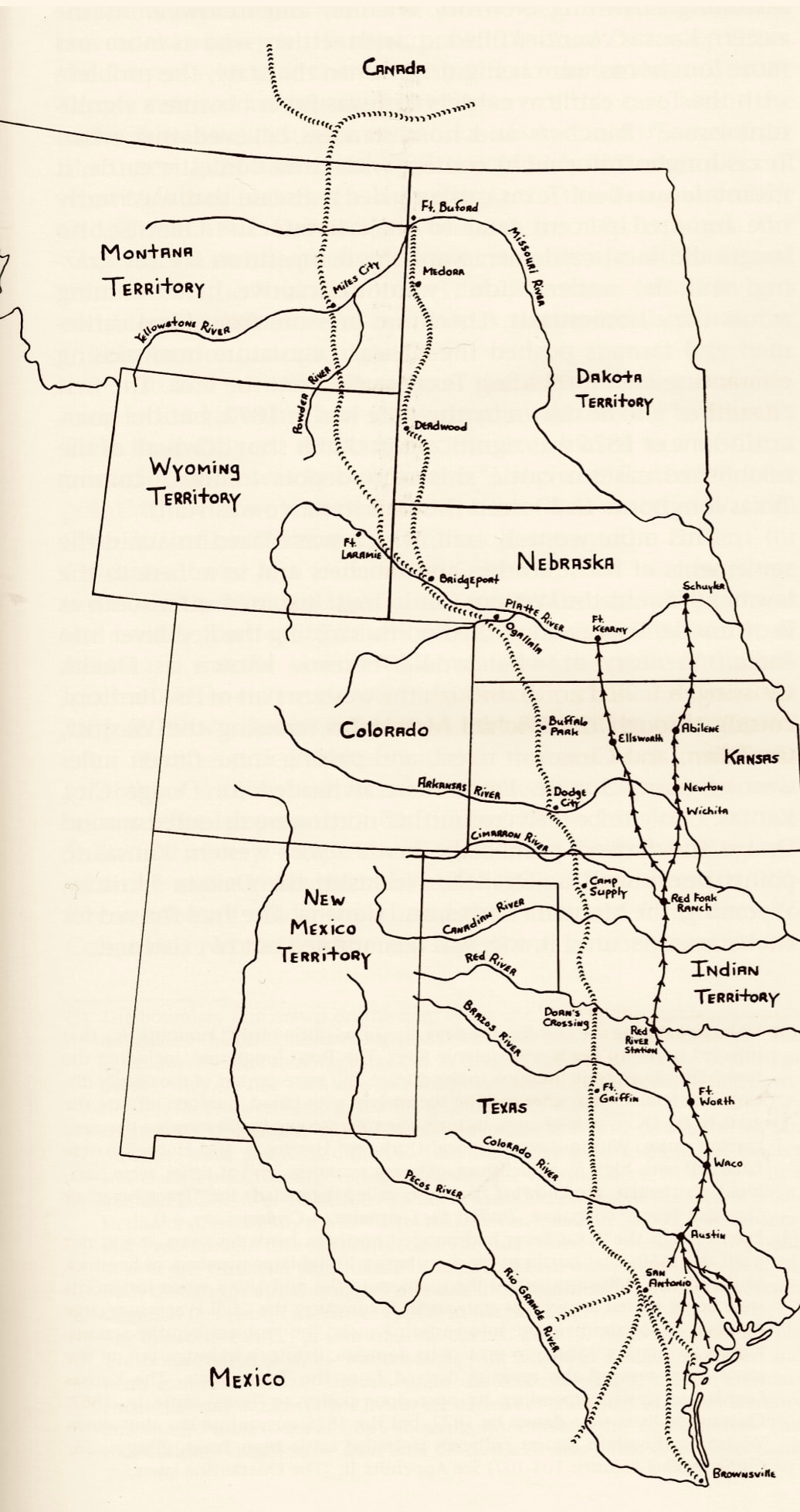

When the U.S. Army successfully concluded the Red River War in early 1875, driving the Comanche and Kiowa onto a reservation, Lytle's trail became the most popular path to the railheads in Kansas and Nebraska. It remained the most used until the cattle trailing industry ended in the 1890s. The Western Trail, a pivotal component of the cattle-driving industry, was also known as the Dodge City Trail or the Texas Trail. It originated in the hill country of Texas near present-day Kerrville, where numerous minor trails converged. During the 1880s, the drives frequently passed by Dodge City, heading to Ogallala, Nebraska, and Wyoming.

In the late 19th century, cowboys faced treacherous terrains, tempestuous weather, and tumultuous cattle stampedes on the wild trails. This era's perilous tales offer a compelling insight into the life of cowboys, including their interaction with Indian territories and their survival against the harsh elements. This blog post takes you on a journey into this historical period, highlighting the dangers these cowboys faced and the courage it took for them to persevere.

The first point of discussion in this exploration is the hazards cowboys encountered on the cattle trails. The cowboys of this era had to contend with terrible roads, rough weather, cattle stampedes, and the need to pass through Indian territory to reach their destinations. Furthermore, they often had to pay tributes to the Indians they encountered as compensation for being allowed to traverse their lands. The picture painted by these cowboy tales depicts a world fraught with danger and uncertainty, yet also imbued with a sense of adventure and discovery.

Navigating rivers was another significant challenge for these cowboys. The narratives of Hiram G Craig and Jerry M Nance, who had to navigate the Washtaw River and Colorado River respectively, highlight the complexities involved in such endeavors. Cowboys had to find suitable crossing points, keeping in mind the water's depth, current speed, and the steepness of the banks. When cattle were swept away by the current, cowboys had to ride along the banks to find the lost animal, hoping it survived the ordeal.

An essential part of the cowboy life was the adherence to the 'Code of the West.' This unwritten code was crucial for their survival. It emphasized fairness, loyalty, and respect for the land. It included principles such as giving enemies a fighting chance, never stealing another man's horse, and never making threats unless they planned on backing them up. The loyalty of the cowboys to their brand was critical as it determined their survival.

In conclusion, the life of 19th-century cowboys was filled with challenges and hardships, but also adventure and camaraderie. Their survival in the harsh conditions of the wild west was a testament to their resilience and adherence to the unwritten 'Code of the West.' Their stories continue to fascinate us, offering a window into a unique period in history where men battled nature and each other to carve out their existence. James Frank Dobie, known as the "Storyteller of the Southwest," was born in 1888 on his family's cattle ranch in Live Oak County. Living both a rugged ranch life and within Texas's centers of education, he taught at the University of Texas, where he developed a course on Southwest literature. Dobie's mission became recording and sharing the disappearing folklore of Texas and the Southwest. He served as secretary of the Texas Folklore Society for 21 years. Dobie was a progressive activist, advocating for African-American student admission to UT in the 1940s. Despite leaving the University in 1947 due to his vocal politics, he continued writing until his death in 1964, leaving behind a legacy that valued liberated minds as the supreme good in life.

“Out in the dry Pecos country, a wagon boss once said to his cook, ‘Scour your pots with sand and wipe ‘em with a rag.’ The cook responded, “Rags all used up, but grass’ll do” ((99).

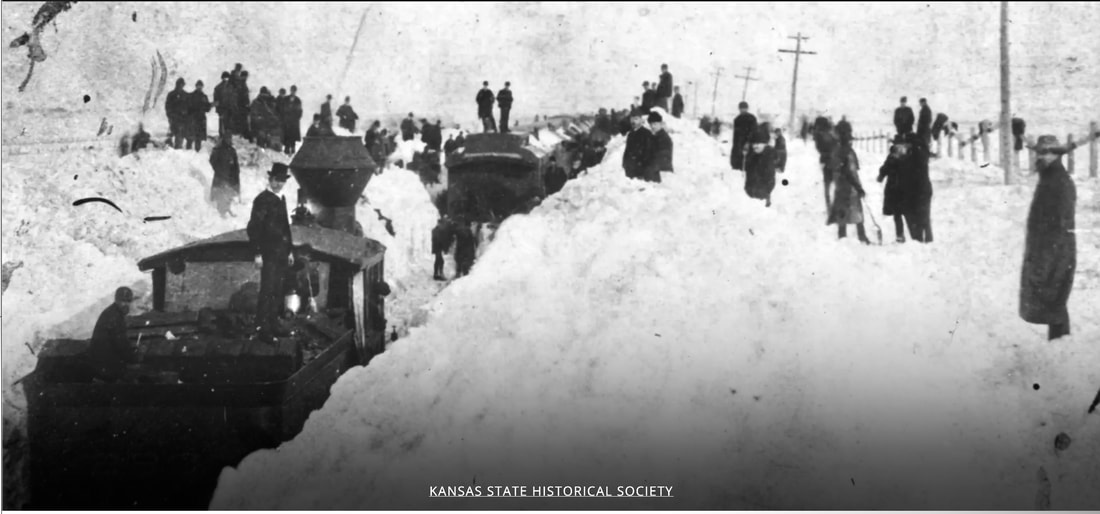

African American Alec Gross was old enough to have white hair. Dobie writes, “Everybody called him Uncle Alec. After he had been out a week with a remuda, he would have the horses following him, instead of him driving them” (113-4). He always carried a whip, but he rarely used it. Dobie writes that many cowboys carried six-shooters, but they seldom used them. He tells the story of his Uncle Frank Byler, who, in the 1880s, finally pulled his pistol out of its holster when he spotted a water moccasin in the water and tried to shoot it. Dobie says, ”The trigger or hammer had become so clotted with dirt and rust that he could not cock the gun....he threw it in disgust at the snake and left it in the mud. He realized, he said, that unless a man could use a six-shooter, he would be better off without it.” Dobie, J. Frank. UP THE TRAIL FROM TEXAS. New York: Random Press, 1955.  When the passengers exited the coach, they discovered they were many miles away from their actual terminus—and that they’d been riding in a coach without a driver. He was, nonetheless, sitting on top of the coach. His rigid, fixed body, that is. As the passengers had bunched for warmth inside the bumpy stagecoach, he had perished in the storm. Original Article By Lynne Hewes "It was January 1886, and the passengers had just lived through the worst blizzard Kansas had ever seen. Trains filled with hogs had frozen solid, along with their living cargo, as they sat idle, prevented from moving forward by drifting snow. People who had been outdoors on the prairie when the storm struck were found frozen, killed while searching for shelter. And then there were the cows—more than 100,000 of them, dead in the storm. All in all, the January 1886 blizzard killed at least 100 people and wiped out about 75 percent of the state’s livestock." When an enormous cold weather disaster hit the Midwest in l886, the cattle industry was already experiencing difficulties. Pastures had been overgrazed, beef prices had fallen, and farmers had begun fencing off some of the open range areas. To add to those problems came the Blizzard of l887. Although there has been snowfall during the fall of l886, what came in January of l887 was the ultimate disaster. PBS created a special about The Blizzard of l887 as part of their New Perspectives on the West Series. According to the series, cattlemen called the blizzard “the Great Die-up.” When temperatures dropped so rapidly that January and the blizzard brought high winds, “some cattle were actually blown over; others died frozen to the ground.” Cowboy Teddy Blue Abbot reminisced about his experience during that blizzard, saying, “It was all so slow, plunging after them through the deep snow that way..... The horses' feet were cut and bleeding from the heavy crust, and the cattle had the hair and hide wore off their legs to the knees and hocks. It was surely hell to see big four-year- old steers just able to stagger along.” Another cowboy, Lincoln Lang, recalled what he saw after the blizzard passed: “...countless carcasses of cattle going down [the river] with the ice, rolling over and over as they went, sometimes with four stiffened legs pointing skyward.” The blizzard and its destruction was the final straw that dampened hopes of many who had aspired to make their fortunes in the cattle business. Mother Nature had proven that her powers were far greater than those of mankind. Source: Photo Reference: The Monster Blizzard That Turned Kansas Into a Frozen Wasteland “Hell without Heat.” New Perspectives on the West, Episode 7. PBS. Public Broadcasting Service, Web. 19 Jan. 2019. IN A BLIZZARD, PAINTED BY FRANK FELLER, CIRCA 1900. DURING THE GREAT DIE-UP, THOUSANDS OF DEAD CATTLE CLOGGED RIVERS, PILED UP AGAINST FENCES, AND FILLED COULEES, AND THE STINK OF DEATH HUNG OVER THE REGION FOR MONTHS. MANY COWBOYS, IN VAIN ATTEMPTS TO SA

Immersing ourselves in the echoes of the American West, we are transported to a time and place where the landscape was vast, and the spirit of adventure was as relentless as the cattle drives that crossed it. This era of the Wild West is often characterized by images of rugged cowboys, but seldom do we acknowledge the African American cowboys who played a pivotal role in shaping the American frontier. These unsung heroes faced the challenges of a post-slavery America, overcoming discrimination and prejudice to carve out their place in history.

One such figure was Bose Ikard, a man whose name became synonymous with resilience and exceptional skill in the world of cattle drives. A former slave, Ikard's life was a testament to the tenacity and fortitude that were the hallmarks of these cowboys. His involvement with the Goodnight-Loving Trail exemplified the critical role that black cowboys played in the cattle industry and, by extension, in the establishment of an integrated national food market during the late 19th century. The tales of these cowboys are filled with the raw beauty and unyielding challenges of the Wild West. They were not just herders of cattle; they were trailblazers in every sense of the word. Multilingual, skilled in entertainment and culinary arts, and sometimes serving as nurses and bodyguards, these cowboys demonstrated a versatility and adaptability that were crucial to their survival and success on the trail. Their camaraderie and the respect they earned from their peers speak volumes about their character and the spirit that fueled their journey across the plains. Bose Ikard's partnership with cattle barons like Charles Goodnight and his ability to handle the most harrowing of situations, such as taming wild broncs or facing down stampedes and elements, is a narrative rich in courage and perseverance. It is a story that also underscores the racial barriers these cowboys faced and overcame. The legacy of African American cowboys is not just a footnote in history; it is a vibrant thread in the tapestry of America's story, urging us to recognize and celebrate the diversity of our shared heritage. The rich imagery of cowboy life, with its connection to the land and the hardships faced, is further evoked through traditional songs and tales of the open range. These stories serve as a powerful reminder of the love these cowboys had for their job, despite the rough conditions and the emotional toll it took on them. It is through these narratives that we gain a fuller understanding of the past and a new appreciation for the hidden faces that have shaped our collective history. By acknowledging the central role that African American cowboys played in the narrative of the American West, we are invited to look beyond the stereotypes and recognize the significant contributions these figures made to the legacy of the West. This episode serves as a tribute to individuals like Bose Ikard, whose life and legacy have become part of American folklore. Their stories, though often overlooked, are as enduring as the landscape they once rode across, forever altering our perception of the legendary American West. As we reflect on the history and legacy of African American cowboys like Bose Ikard and Nat Love, we are reminded of the importance of reclaiming this diverse heritage and honoring the true diversity of the characters who forged the American West. It is through this exploration and celebration that we ensure the spirit and stories of these cowboys continue to echo through time, inspiring future generations to acknowledge and learn from the richness of our history. The Kansas Cow Town grew out of necessity to satisfy man's needs. In addition, cattle were to provide these towns with their chief means of support in the two decades the cattle business endured. During this time, some five to six million cows parted through the myriad shipping points on their way to the market. Of the many towns that grew up around this thriving enterprise, only four or five ever received national prominence as wild and woolly cowtowns. One is Dodge City.

The few existing settlements catered to the appetites of buffalo hunters. Dodge City, Kansas, called initially "Buffalo City," was an example. New contenders within the new settlement acknowledged that the buffalo were disappearing and that the buffalo-hunter town needed a new raison d’être (a purpose for making a living), or they would die. The business leadership of Dodge City vigorously advertised the town's wide-open character, its open range, and its flexible enforcement of laws regulating gambling, prostitution, and public drunkenness. It already had a full-bodied gambling, drinking, and prostitution infrastructure to nurse the buffalo hunters, and it was just a matter of discovering new customers. This would be the cowboys associated with the cattle drives coming up the newly established Western trail that would provide prosperity. When they learned that Dodge City's preparatory role was to serve as a supply point and way station for herds, city organizers mustered to form future business ventures to keep the cattle drives from circling the western end of town; a plan was needed to lure cowboys into local establishments before moving on to Ogallala. As the cattle-shipping season of 1876 loomed, Dodge City townsmen braced for a new economic opportunity. They formed a special council on Christmas Eve of 1875. This particular council of businessmen men met to appoint provisional officials. These selected men were to hold office until a municipal election was planned for the following April. The special counsel immediately parted in differences, and on Christmas Eve of 1875, Dodge City became a divided town. The division came when one of the members of the individual committees proposed the idea of ordnances. He stated, "We should have an ordinance prohibiting the firing of guns within the city limits. He continued to make his point by stating, "I also believe we should have a law not allowing the riding of horses over sidewalks and into the saloons." A bitter debate broke out. Those businessmen who hungered after the cattlemen's trade strongly opposed any restrictions on the Cowboys. This side of the discussion feared the cattlemen would look elsewhere for a shipping point. Heading this group was Bob Wright, the former Fort Dodge sutler, whose general store partnered with Charlie Rath, one of the first businesses established in Dodge City. In 1876 and for many years, Bob Wright was Dodge City's most prosperous businessman. Allied with Wright were James H. ("Dog") Kelley and his partner, Peter L. Beatty, proprietors of the Alhambra Saloon, Gambling Hall, and Restaurant. George B. Cox, another early arrival, always sided with the Wright forces. Cox came to Dodge City from Larned in 1872 and built the thirty-eight-room Dodge House, which opened on January 18, 1873. Opposing the Dodge City Gang was a group of men who proclaimed to stand for law and order, led by wholesale liquor dealer George M. Hoover. Physician Sam Galland, lawyer Dan M. Frost, and livery stable owner Ham Bell were preeminent in this faction. Hoover was a Dodge pioneer, having sold whiskey to the soldiers from Fort Dodge in a tent on the townsite as early as 1871. Galland, Frost, and Bell did not establish residence until 1874. However, early settlers Wright, Kelley, Cox, and others considered them johnnies-come-lately and resented their attempts to change the town's character. Peter L. Beatty was selected as acting mayor. Beatty served as Mayor from the December 1875 meeting of town leaders until April 1876. Dodge City, however, was about the limit of westward shifts of the cattle drives. Dodge was in the middle of the prairie, providing thousands of acres of grassland for cattle to fatten on while they waited for their trains to the East and recovered from the cattle drive to Dodge. Fredric R. Young, in his book "Dodge City: Up through the Century," explained in 1972 an advertisement that appeared in the Dodge City Times as a means to draw the cattle trade to Dodge City:

From there, they drove to the Pecos River and followed its course to Horse Head Crossing. After crossing the Pecos, they followed its west side to the North Spring River in New Mexico and gradually swung toward the Raton Pass, crossing the mountains and driving north to the Arkansas River. They held the herd for three months in the Garden City territory and then worked down the Arkansas to where Ingalls is now located.

"That was before the railroad reached Dodge City, although much of the railroad grade was partly completed to the west line of Kansas. Large crews were working on the grade, and a ready market was found for the cattle. "When they reached what is now Ingalls, Kansas, they found a large corral still standing on the river flats just east of where the present Ingall's bridge now crosses. There were also the remains of Soddies and Dugouts as well as the remains of a few Dobies on the river bottom just north of the corral, for there was the regular campground of the old Santa Fe Trail, which crossed the Arkansas River at what was known as `The Cimarron Crossing' of Arkansas. Doc says the crossing was just west of the north end of the present bridge, although the crossing was not used then and had not been for some time because of the Indians to the south and west. The regular trail went up the Arkansas River, and the Cimarron Crossing was not again regularly used.

The narrative of the American West is rich and complex, yet one aspect that has been overshadowed is the contribution of Black American Cowboys. These men, emerging post-Civil War, found autonomy and respect that contrasted starkly with their lives in the South. Their expertise in cattle management and trailblazing roles was indispensable in the expansion of the cattle industry, and yet their tales remain largely untold. Roughly one-quarter of 19th-century cowboys were Black, a statistic that surprises many due to the lack of representation in popular culture.

The podcast episode not only uncovers the general history of these cowboys but also zooms in on the life of one particular cowboy, Nat Love, whose adventures epitomize the experiences of many Black cowboys. Love, born into slavery, would become a legend in his own right, known as Deadwood Dick. His memoir offers a first-person perspective of a Black cowboy's life, filled with danger, adventure, and a journey towards self-discovery. Through the podcast, we traverse Love's path from the plantations of the South to the open ranges of the West. We witness his early struggles and the remarkable moment when he tamed a wild horse, leading to his hiring by a Texas cattle company. The episode delves into his encounters with Native American tribes, his ascension through the ranks of the Gallinger Ranch in Arizona, and his extraordinary skills that earned him the nickname Red River Dick. The resilience of these cowboys is evident as we recount the various roles they assumed beyond herding cattle. They were multilingual trail cooks, entertainers, and sometimes even served as nurses and bodyguards. The episode sheds light on the discriminatory challenges they faced, but also the respect and camaraderie they earned from their peers on the trail. We also explore the cultural significance of the term "cowboy" and its transition from a term of contempt to one of respect. Furthermore, the podcast delves into the contributions of these cowboys to the Western cattle trails, their roles in the great cattle drives, and the skills they brought from their African heritage that proved invaluable in managing the vast herds of cattle that roamed the American plains. As we navigate the history of these cowboys, we also pay tribute to the courage and spirit that characterized their lives. The episode concludes by reinforcing the central role that Black cowboys played in the narrative of the American West and celebrates their legacy, which has been long overdue for recognition. The episode is a testament to the rich tapestry of American history and the diverse characters who shaped it. It is an invitation to look beyond the stereotypes and acknowledge the significant contributions of Black cowboys to the legacy of the West. Through stories of individuals like Nat Love, we gain a fuller understanding of the past and a new appreciation for the hidden faces that have shaped our collective history. |

Author"THE MISSION OF THE WESTERN CATTLE TRAIL ASSOCIATION IS TO PROTECT AND PRESERVE THE WESTERN CATTLE TRAIL AND TO ACCURATELY PROMOTE AWARENESS OF IT'S HISTORICAL LEGACY." Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed